In January 2018, ESPA invited me to present the results of a report synthesising evidence for the

contribution of climate smart agriculture to poverty alleviation. The workshops

in Kenya and Malawi involved stakeholders from the country teams of EBAFOSA– the

Ecosystem Based Adaptation for Food Security Assembly.

Our synthesis suggests that scaling up climate smart agriculture

would probably work best (in terms of larger scale) with commodities that would

attract interest of private sector. However, such commodity value chains are

often not accessible for the most vulnerable, who lack land, transport and

other means to participate in this trade. As such, scaling up climate smart

agriculture may fail to ‘leave no one behind’, in the spirit of the Sustainable Development Goals.

The meetings in Kenya and Malawi brought some interesting

questions to the fore: there was a shared sense that climate smart technologies

exist, but that knowledge has to be synthesised and spread in each country.

However, relatively little discussion focussed on how to involve the most

vulnerable in it due to the focus on quick success that NGO financing

mechanisms force? Or to silos in which governments, experts and NGOs operate?

Or the fact that many smallholder farmers are ‘poor’ to begin with? And should

(climate-smart) agriculture be inclusive, or should other welfare instruments,

such as social benefits, take care of the most vulnerable people?

In both countries, the need to involve agricultural extension

officers (in charge of delivering information about agricultural practices to

farmers) in raising awareness of climate-smart practices was high on the

priority lists. But there are so many changes that go against decades of

‘traditions’ in farming (parentheses added because of the political forces that

drove ridging practices). How to change practices from ridging all land for

maize cropping, to irrigation in the wet season (insufficient rain) or

multi-cropping for resilience and food security? How to adapt prescriptive,

rigid methods to flexible, place-based and modern approaches in countries where

rural youth may soon create labour shortages?

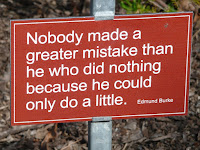

Finally, the question was posed – should upscaling be based on

farmers’ needs, or on where ‘experts’ or ‘leaders’ think that they ought to go

in the face of climate change and other social-ecological drivers? Leading by

example may be better than just talking, but it is not sufficient – how can one

stimulate more widespread adoption, beyond the lead farmer along the road? This

ties in with some of the pushback from civil society organisations, trying to empower

smallholder farmers.